Over 16 years of street style, captured in various towns around the world.

Month

- February 2026 12

- January 2026 21

- December 2025 23

- November 2025 19

- October 2025 22

- September 2025 22

- August 2025 21

- July 2025 24

- June 2025 20

- May 2025 22

- April 2025 22

- March 2025 21

- February 2025 20

- January 2025 20

- December 2024 15

- November 2024 21

- October 2024 21

- September 2024 21

- August 2024 16

- July 2024 16

- June 2024 19

- May 2024 22

- April 2024 22

- March 2024 18

- February 2024 19

- January 2024 17

- December 2023 10

- November 2023 18

- October 2023 18

- September 2023 15

- August 2023 21

- July 2023 21

- June 2023 20

- May 2023 21

- April 2023 20

- March 2023 20

- February 2023 20

- January 2023 19

- December 2022 16

- November 2022 22

- October 2022 20

- September 2022 13

- August 2022 14

- July 2022 11

- June 2022 12

- May 2022 13

- April 2022 11

- March 2022 13

- February 2022 8

- January 2022 10

- December 2021 7

- November 2021 12

- October 2021 11

- September 2021 22

- August 2021 22

- July 2021 23

- June 2021 18

- May 2021 17

- April 2021 17

- March 2021 23

- February 2021 14

- January 2021 15

- December 2020 19

- November 2020 9

- October 2020 11

- September 2020 9

- August 2020 11

- July 2020 15

- June 2020 13

- May 2020 3

- April 2020 1

- March 2020 16

- February 2020 19

- January 2020 21

- December 2019 9

- November 2019 21

- October 2019 23

- September 2019 18

- August 2019 22

- July 2019 23

- June 2019 19

- May 2019 23

- April 2019 21

- March 2019 20

- February 2019 19

- January 2019 19

- December 2018 14

- November 2018 21

- October 2018 22

- September 2018 21

- August 2018 23

- July 2018 29

- June 2018 21

- May 2018 23

- April 2018 20

- March 2018 22

- February 2018 20

- January 2018 19

- December 2017 17

- November 2017 22

- October 2017 23

- September 2017 21

- August 2017 23

- July 2017 22

- June 2017 22

- May 2017 23

- April 2017 19

- March 2017 23

- February 2017 22

- January 2017 17

- December 2016 10

- November 2016 21

- October 2016 23

- September 2016 28

- August 2016 26

- July 2016 24

- June 2016 20

- May 2016 25

- April 2016 22

- March 2016 30

- February 2016 30

- January 2016 22

- December 2015 25

- November 2015 44

- October 2015 50

- September 2015 46

- August 2015 45

- July 2015 38

- June 2015 39

- May 2015 36

- April 2015 56

- March 2015 43

- February 2015 29

- January 2015 36

- December 2014 28

- November 2014 25

- October 2014 32

- September 2014 36

- August 2014 30

- July 2014 41

- June 2014 37

- May 2014 36

- April 2014 39

- March 2014 29

- February 2014 39

- January 2014 34

- December 2013 32

- November 2013 56

- October 2013 45

- September 2013 45

- August 2013 35

- July 2013 18

- June 2013 23

- May 2013 31

- April 2013 60

- March 2013 39

- February 2013 25

- January 2013 23

- December 2012 12

- November 2012 18

- October 2012 28

- September 2012 34

- August 2012 22

- July 2012 26

- June 2012 16

- May 2012 27

- April 2012 15

- March 2012 14

- February 2012 22

- January 2012 14

- December 2011 24

- November 2011 24

- October 2011 32

- September 2011 53

- August 2011 18

- July 2011 6

- June 2011 8

- May 2011 13

- April 2011 13

- March 2011 16

- February 2011 18

- January 2011 7

- December 2010 4

- November 2010 5

- October 2010 3

- September 2010 3

- August 2010 4

- July 2010 1

- April 2010 1

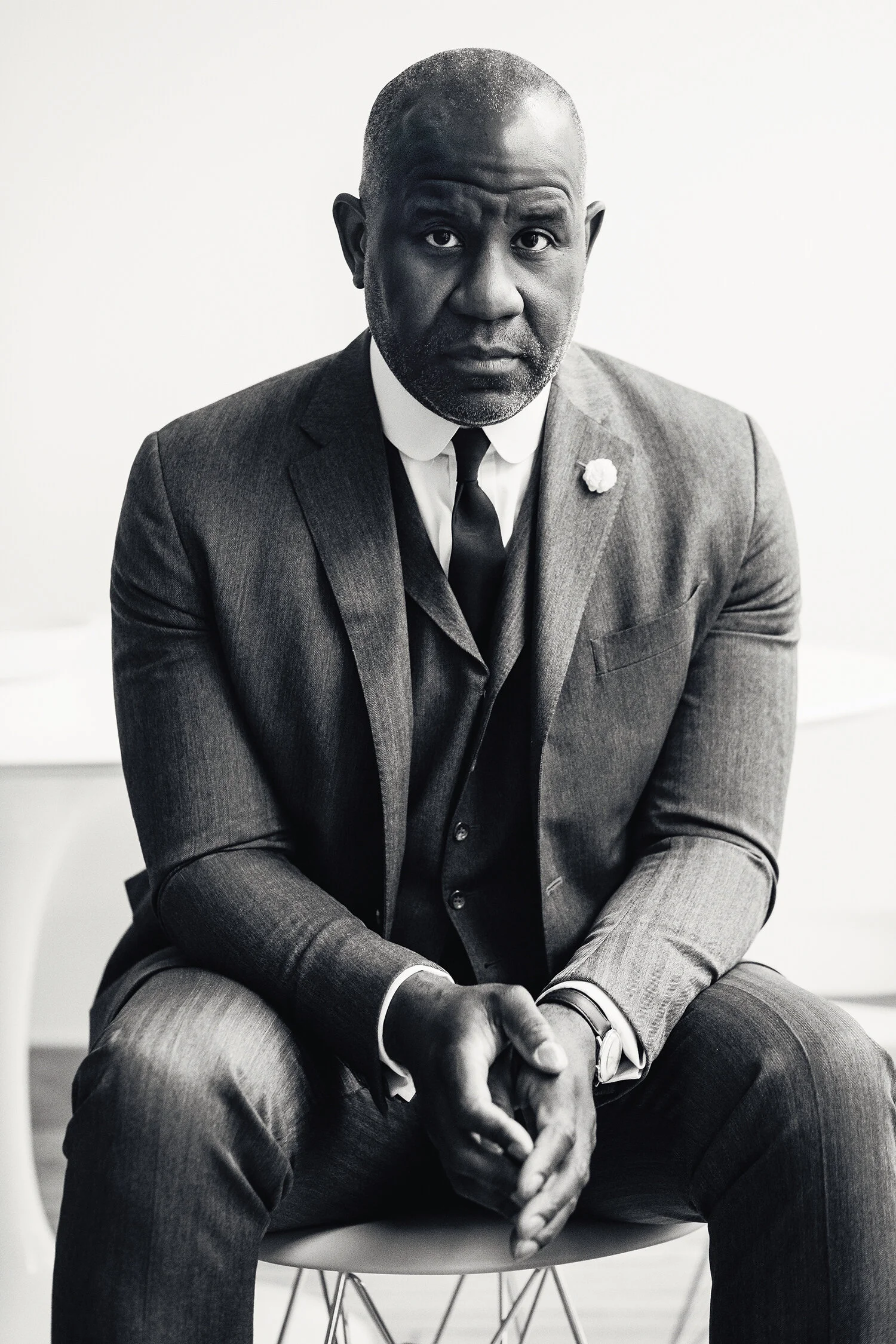

Wyatt Mitchell in New York

Wyatt Mitchell in New York

Published in print, June 2015.

Words by Dan Rookwood

Photography by David Urbanke

Wyatt Mitchell is not just a New Yorker, he is The New Yorker. As the iconic magazine’s first creative director in its 90-year history, he is the aesthetic custodian of a much revered and respected literary institution. Mitchell is also the best-dressed man at Manhattan’s most fashionable address—One World Trade Center, the new home of Condé Nast magazines— which is where MITT met with him.

“If I drink a coffee, I might die,” says Wyatt Mitchell while perusing the barista’s menu. “Seriously. My heart can’t take caffeine. But I will have a herbal tea.”

We are sitting in the Condé Nast cafeteria on the 35th floor of the tallest building in the western hemisphere, the newly opened glass-and-steel 1,792-foot exclamation point that dominates the skyline where the Twin Towers once stood.

This cafeteria is the hallowed water-cooler where editors and creatives of the world’s most powerful and iconic magazines—from Vogue to Vanity Fair to GQ to, yes, The New Yorker—congregate to chew anything but the fat. A fashion fishbowl, it thrums with Prada-wearing devils power-lunching on their vanity fare of kale and quinoa salads and pressed juices.

The coolest man in the room is Mitchell. On the day we meet, the six-foot-something 48-year-old is wearing a daring double-denim combo of indigo chore jacket and jeans with a white dress shirt and black tie—an unusual high-low ensemble, but it works. The look is accessorised with a silver tie slide and poking out from his chest pocket is a pencil sharpened to a spike. He looks just as sharp.

Mitchell is more usually attired in a suit—often a three-piece—worn with a hat except during the sticky heat of a New York summer. He wears his shirts buttoned up—sometimes with a tie, sometimes with a bow tie, often without a tie at all.

“I work at The New Yorker, which is a respected institution, and I want to do it proud, so I account for that in my style,” he explains. “I like a turn-of-the-century look. I think there was a certain decorum with dressing in suits and hats back then. I like the idea that men who wore suits every day had a respectability about themselves, a respect for work, and a respect for other people.”

“Wyatt is a gentleman from another age, an old soul in a young man’s body,” says his friend and former boss Scott Dadich, the editor-in-chief of technology magazine WIRED. “He has such a singular style, sort of a timeless mash-up of Boardwalk Empire meets Cool Hand Luke: textural mixing with classic pieces and odd flourishes. I couldn’t pull off half of what he wears, but I do aspire to being as comfortable in suits as he is.”

Up until carrying out a recent inventory when he moved apartments, Mitchell owned more than 70 suits

—a lifelong collection. He’s since edited it back to 41. “This is the embarrassing part about being my age: many of those suits I could no longer wear. I just had an attachment to them in the hope that one day I lose some weight and I can put them back on. Of course, I’ve kept a lot of them because I love those suits. I love them.”

Mitchell describes his wardrobe as organised and orderly but not obsessively so. His new apartment, a short walk from Union Square, is a clutter-free haven of clean modern minimalism. “I live in a crazy city so I like to treat a home as a kind of quiet, peaceful, reflective sanctuary,” he says. “I need the room cleared to breathe. I like space.”

What does the creative director of The New Yorker—a man with direct access to some of the world’s best photographers, illustrators and artists—choose to have on the walls of his apartment? “More than anything I have photographs of jazz musicians. I have a wonderful picture of Bill Evans, the piano player, taken by Jim Marshall, which I was lucky to get before Jim passed away. It is signed by him and it is beautiful—one of my most treasured things. I have a Frank Sinatra photo, I have a Duke Ellington photo, I have a Dizzy Gillespie photo …”

Music is Mitchell’s great passion in life, jazz in particular. For a long time when growing up, he worked in record shops. “I’m one of those people,” he says. He feels that today’s instant, easy access to limitless music via digital services such as Spotify has diminished the experience of personal discovery.

“I spent so much of my life finding music. Part of the enjoyment was not just listening to it, but the searching for it in the first place. I remember looking for a Nick Drake box set—what’s it called? Fruit Tree—on vinyl, which was really hard to find. I finally found it and I just could not have been happier that day. It must have taken 10 years to find that. I have now digitized all my music, but I’ve kept any CDs or records where there was a journey or a difficulty in finding the artefact.”

Mitchell has also taught himself to play various musical instruments over the course of his life. “I played the trumpet unsuccessfully in high school. And then I was fascinated by the bass guitar and taught myself that for a few years. Now I play the piano, and my goal is to slowly teach myself jazz piano so that, at the point of my death, I will be at my best … just as I sort of drift off. I have no ambition to have a gig, but I do want to get better and better and better.”

“He should be in a jazz band,” says Dadich later over email. “He’s too modest, but very, very good.”

Growing up as an only child in small-town Ohio, Mitchell spent a lot of time by himself. There is a theme running through his life of picking things up that interest him, spending time learning to work them out, giving them a go. This is how he got into the world of design in the first place. “Yeah, I did not go to art school at any point,” he explains. “I remember that one day someone came in with a Macintosh computer and said: ‘We need a desk to put this on. We can’t find a place to put it.’ I said: ‘Put it in my office.’ Only because I liked the idea of swivelling around in my chair between my two computers. So they put it in there and I played around with it and started to learn some of the software and thought, ‘Wow, this design stuff is kind of cool!’ And that’s how I began on the path.”

Up until that point, Mitchell had been working as a quantitative analyst—an economist—crunching numbers. It sounds a million miles away from design, but Mitchell can see a parallel between the two disciplines. “To me, they’re very much the same idea,” he says. “A magazine story or, indeed, an entire magazine is a complex mix of data. It needs someone or a group of people to synthesise it and make it presentable and digestible so that the reader can enjoy it without finding it overbearing and oppressive.”

He moved into working on the production side of publishing on magazines such as DETAILS, Vibe and Esquire, picking up tips from the magazines’ designers as he went. With no formal training, he learned on the job until he was skilled enough to transition into design.

It’s an approach that has served Mitchell well. “He’s self-taught in so many ways, and with it comes a natural boundary-busting tendency,” says Dadich. There is a freedom of expression and approach that comes with someone who has natural flair rather than strictly trained ways.

To date, he has amassed an impressive 70 awards, including an unprecedented three consecutive design ASMEs (the award of the prestigious American Society of Magazine Editors) and three consecutive Society of Publication Designers “Magazine of the Year” titles for his innovative work at WIRED.

His current job would seem much more restrictive on the (type)face of it. He is tasked with modernising and evolving a venerable old title while retaining its visual character and DNA. Does he find it creatively inhibiting? “The New Yorker is the perfect job for me right now, after having been at WIRED, which was much more free, much more innovative, much more experimental,” he replies. “This is a job where I’m not designing for awards or for flash or for self-recognition; I’m designing to make this iconic brand better.”

No more free-form experimental solos; now he’s playing the well-known jazz standards. “This job is about the improvement of something that is revered and regarded and isn’t broken. So, it’s a more thoughtful, smarter type of design and, in some respects, more delicate, because mistakes have a larger effect with a brand like The New Yorker. At WIRED, you can make a mistake and then, next month, you try something different and readers expect that or understand that. The New Yorker readers are not as forgiving.”

From Mitchell’s office window, he enjoys a toy-town view of lower Manhattan and the Hudson River. “The window is perfect,” he says. “I draw a lot of inspiration from looking around me, aware and observing. I get most of my creative inspiration from just walking around, being on the subway, overhearing a conversation, listening to music, seeing this movie, just living. Part of my job is about creativity and, therefore, I have to give some room for that to sort of bubble up.”

The musical riff returns. Mitchell likens his job as a brand leader to being a jazz bandleader. “I want people to understand what the mission and philosophy is behind what we’re doing—then improvise.”

When does he do his best work? “I think better in the morning. I have brilliant ideas in the shower. I’m at my clearest. But I might be more creative in the evening time with music playing. I think there can be a distinction between the two.”

Just don’t give him any coffee.

END

Love Letter: Modern Jazz Quartet

Love Letter: Modern Jazz Quartet

Published in print, September 2019.

Words by Gabriel Jermaine Vanlandingham-Dunn

It was around 2004 that I was invited to an intro photography class at a local community college in Baltimore, Maryland. My dear friend, the late Alan Rutberg, taught the class and he’d asked me to talk with his students about album cover photography and how powerful it could be. Having collected records, mainly jazz, for most of my life, he felt that my background in Africana Studies would help his students understand how art reflected and impacted the Black American experience. I was honoured by his request and knew exactly which record I wanted to talk about. I arrived to the class with a beautiful copy of the Modern Jazz Quartet’s self-titled LP (Atlantic, 1957) in my bag.

I wish I could tell you exactly how I came to know the MJQ. It might’ve been me stumbling upon a copy of Milt Jackson With John Lewis, Percy Heath, Kenny Clarke, Lou Donaldson And The Thelonious Monk Quintet (Blue Note, recordings from 1948 and 1951-2, released in LP format in 1955). Or maybe it was my former boss hipping me to their airy masterpiece Space (Apple, 1969). But more than likely it was the constant search for samples used in my favourite hip-hop songs that got me to know them (Pete Rock, No ID, DJ Premier and Diamond D made good use of their spacious sound). I could easily nerd out on them for days, but I’ll drop a few facts and get back to my story.

The group was founded around 1952 with John Lewis on piano, Milt Jackson on vibraphone, Percy Heath on bass (who replaced Ray Brown) and Kenny Clarke (who was replaced by Connie Kay in 1955). Lewis and Jackson (along with Brown and Clarke) played together in Dizzy Gillespie’s large ensemble and first started playing as the Milt Jackson Quartet. Their sound was unique, marrying the jazz and blues experience with euro classical sensibility. For this, all listeners didn’t love them. In fact, when Kenny Clarke departed the group, he left emphasizing that he couldn’t stand playing the music anymore. Yet they became very popular for their special renditions of standards and original compositions such as Django, Bag’s Groove, Ralph’s New Blues, Fontessa and La Rhonde. The switch from the independent Prestige label to the major powerhouse Atlantic Records in 1956 brought the group to a wider audience and allowed them to tour internationally.

I explained some of these things to the (mostly teenage) students that afternoon, but they didn’t seem to understand the significance, until I reminded them about the era in which the MJQ came about. Although no period has been easy for us Black folk in the States, the 1950s in particular were no joke. There were many changes happening around the world, and while many white families were enjoying the expansion of the middle class, the civil rights movement began in earnest. The students and I made a brief timeline to create a better understanding of the importance of representation concerning Black folk during the time when the biggest stars of the day were Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley. With all this in mind, I then asked them to look at the self-titled cover, emphasizing its production in the year 1957.

The first word that comes to mind is dignity. These beautiful brothers are dressed sharply in dark suits (very rarely did you see them not wearing perfectly fitted three-pieces). The backdrop of the shot is a dark maroon that matches their ties. Fresh haircuts align their domes, while Lewis and Heath sport full beards. Jackson looks extra professorly with his specs (like the style worn by Malcolm X). All eyes are locked on photographer Fabian Bachrach’s lens. In short, these brothers did not come to fuck around. Though their music was perceived as commercially aimed, they were not only serious about their craft, but also their image as Black men in America. In a decade where many jazz musicians were getting their cabaret cards revoked (a racist system that deserves its own essay) and being limited to gigging for pennies, these cats began touring the world, representing the greatness of Black men’s strength and beauty in the process.

When breaking down these observations to the class, it made more sense to them why I’d connected with the image. Growing up there were plenty of positive images of Black men in my community, yet the media mainly perpetuated stereotypes and criminality. During the era that gave birth to the television, album covers mattered very much. The artwork not only sold a product, but it also allowed artists — those lucky enough — to be seen as they wanted to be seen. This text-less cover comes across as a triumph of the day; a salute to the ancestors, but also a cementing of a long-lasting presence of Black genius. The Modern Jazz Quartet played together for almost 50 years, taking breaks while each member recorded plenty of material outside of the group. I can’t help but think that this image, along with their lengthy discography, inspired many more brothers to make sure that they are seen and heard with respect, on their own terms, every place that they travelled.

END

His Words

His Words

Published in print, March 2018.

Words by Gioncarlo Valentine

Photography by Gioncarlo Valentine

Joel L. Daniels is the kind of writer that pushes the medium by shifting and refining what poetics can do. He’s the type of writer who agitates traditionalist notions and wields the import and impact of language with ease. But what’s most encapsulating about Joel is his personality. He is all soul, all the time. Smiling that big smile and emanating a warmth that feels like something ancient and deeply Black.

Growing up in The Bronx, New York, Joel was involved in a little bit of everything. He started out as an emcee, rapping in a style that was some parts Jay Z, some parts Nas, but somehow all parts Joel. Like so many young Black men, he rapped from a desire to escape, to express. Making music under the name MaG, he told the stories of his childhood, his complicated relationship with his father, and the all-too-familiar struggles of growing up Black and poor in America. His lyrical brilliance led to a deep appreciation for language and for performance. In 2013 he won The Bronx Recognizes its Own poetry grant from The Bronx Council on The Arts, and after graduating from Temple University he started performing his poetry around the country and shaping his voice as a writer.

Since then Joel has written for The Boston Globe, The Huffington Post, Philadelphia Print Works and Medium, where Joel currently has more than 35,000 followers. His succinct, cripplingly beautiful poems, and his incredibly vulnerable essays touch on everything from Blackness, childhood sexual abuse and misogyny, to his beautiful daughter Lilah.

Last year saw the release of his first book, A Book About Thing I Will Tell My Daughter (Bottle Cap Press). The book is a small, inimitable collection of poetry, essays, and genre-defying writing meant to be passed down to his two-year-old daughter. The writing is smart, poignant, honest and witty.

I recently had the great pleasure of sitting down for an interview and photo-shoot with Joel. Half business, half gut-busting, ugly laughter, we got to discuss his creative praxis, where he sources his inspiration, and his most inspiring role — as Lilah’s father.

Gioncarlo Valentine: Why do you write? You are an incredibly creative person, so what drives you to use language as your medium?

Joel L. Daniels: Thank you, really. Writing started as a means of love for myself, learning how to love myself more through words. Also, to get girls. The former I have been fairly successful at. Now, I write for little Black boys who look like me, who grew up where I grew up, who are looking to see themselves in someone. I write so I can tell stories. I write for my father, because America owes him. I write so my mother can have her co-op. I write for my daughter. I write to save myself. Language gives me power, it allows me to express myself in ways that give me strength, and give others strength in the process.

Who are the writers that challenge you and push you to expand?

Eve Ewing, Gioncarlo Valentine, Shefon Nachelle, Ashley Simpo. They all happen to be writers of color, and do this thing with language that is sexy and scary, amorphous and fucking beautiful.

What does fellowship look like to you as a writer and how important is it?

It’s everything. Even just via social media, having something of a village of like-minded creatives who push and challenge me as a writer is a big part of keeping me motivated, in search of new techniques and new ways to explore the ways in which I use language to convey a message.

Have you read any parts of the book to Lilah? Does she approve of your writing styles?

Lilah will approve of anything if I put a chicken nugget in front of it. Right now, Lilah only cares about the cover of the book, and keeps saying “Lilah swings” every time she sees it, so I think the book is really resonating with her on a personal level.

Tell me about co-parenting. What are the most difficult parts and what are the more rewarding ones?

As with any relationship, the biggest issue is communication. For me, I realise the clinging and attachment I have to certain things, and how when those things aren’t met in the ways I see fit, I can travel to another place in my mind and body that is not conducive to a healthy and stable partnership in parenting. The rewarding parts are when I can see and feel us getting it right, it feels like an out-of-body experience; effortless and seamless.

Your career is certainly just getting started, but it is on the rise. What are your biggest fears, as a parent, about the success you envision for yourself?

For me, not being enough for my daughter really is kind of a nagging fear. Providing her with all of this soon-to-be financial security but maybe not being around enough once things start to really pick up. But, it’s not really a worry, if I’m honest. I know the kind of father and parent I’ve always wanted to be, and that’s the kind that doesn’t miss birthdays or recitals or shows or whatever other events that will matter to her down the road. I know what choices I will make. They almost always include her in them, or at least being sure I can work around whatever I need to do to be there in some way, shape, or form.

As a writer, rapper, creative and father, how do find balance? How to do you manage to do it all?

No such thing as balance. It’s a MYTH! Nah, really though... I just do, ya’ know? Everything is seasonal for me — I was emceeing and then I kind of stopped; the same with film and theatre acting. There has been a constant ebb and flow. I was taking photos almost every day for like six months. I’m always a father — some days I’m less attentive than others, but I’m present. I show up wherever I need to be, whether that’s to the children’s museum or to a workshop. It’s really about maximising time and opportunity, and doing all with as much smile as possible, and just being present for whatever truth shows up in the middle. Balance is something old white men created to make folks feel guilty about wanting to have a life that exists on multiple planes outside of the stale-ass rhetoric they’ve been feeding us in school and self-help books. Live ya’ life.

I imagine like most writers you experience periods of writer’s block. What methods do you use to get through it?

For me, it’s just immersing myself in the world — calling or hanging out with friends, reading a good book of fiction, a museum, a library or bookstore, meditative walking, people watching, people listening, new music I can vibe to (hella inspiring,) taking myself out to the movies or dinner, hitting an art gallery... anything that involves people and art and solace.

What makes you feel the most insecure as a writer?

Other writers, ha! The competitive emcee in me wants to roast and vaporise all other writers I love, but also love up on them and make them tea or coffee or whatever their preferred beverage is. Even as a grown adult, the thirteen- year-old middle schooler in me still has a bit of envy when I see other writers racking up bylines and accolades; it serves as a reminder for the work I still need to do and how far I have to go. It is also incredibly silly and egotistical. I’m constantly working on it, though. I promise.

When do you feel the most beautiful? I always try to ask this question when I’m interviewing Black men because I don’t think we think about that enough and it’s incredibly invaluable.

It feels corny sometimes, but when I’m bathing my daughter. I feel like I’m bathing Jesus, if there was a way to describe that. So really, I feel most beautiful when giving myself to others willfully, without regard or worry as to the outcome. Bathing my daughter is the closest thing to heaven, I suppose.

Give me three mantras/quotes that you live by?

“Do the work.” “Trust the process.” And, less of a quote, but more of a question, “Where is there an opportunity for me to add more love to this situation?”

How do you measure your growth as a writer?

Hmm, a very good question. I think, when I look back at my earlier writings, I want to feel like the language is evergreen, and reflects, not a time, but a breadth of skill and knowledge commensurate with my experience as a human. It’s hard to measure something like that, but I know it when I see it and feel it.

What projects are you working on in the next few months?

Does being a better human count as a project? I hope so. Nah, working on a memoir, which feels very weird and almost pompous at thirty-five but whatever, I’m grown, I do what I want. I have an agent and stuff so I have to like, write for deadlines or whatever, so that’s cool. Ummm, this collection of flash-fiction kind of stories, a photo-essay-poetry book thingy I’m trying to finish, and Lilah. Yes, my daughter is a project — how successful can I be with putting all the love I can muster into a person. I’ll let ya’ll know how it turns out. Or rather, she will when she’s holding down the Oval Office.

END

The Rise of Ziggy Ramo

The Rise of Ziggy Ramo

Published in print, March 2018.

Words by Erin McFadyen

Photography by Bryce Thomas

Adjacent to a BP service station in Bondi, passers-by with their takeaways stop to look at Ziggy Ramo. He’s standing on somebody’s front fence in double denim, having his photograph taken while he explains to us his ways of living and thinking. Hailing originally from Perth and rapidly ascending in an industry that whisks him around Australia and around the world, we’re lucky to catch the musician for a moment in Sydney, where he’s recently set up house. Roaming the streets of his sun-soaked new home, we talk writing, women in hip hop, dressing and vegetables. Ziggy’s a restlessly prolific artist. He’s a thinker of inimitable compassion, a second-hand store devotee, and also a hugger.

Erin McFadyen: Can you tell me a little about your writing process?

Ziggy Ramo: I write the majority of my music with a writer called JCAL. We live together now too, actually. He’s one of my best friends.

Were you pre-existing friends or did you meet through music?

We met through work and just became really close. He does a lot of live stuff with me as well. He’s an amazing artist and we have a great connection writing-wise. We write really quickly, and we write more stuff than we need for my project. So, my manager suggested I write for other people as well. I think the biggest struggle as an artist is that you write a song, but it will take months at least for that song to actually be released. Most of the music we’ve put out had been written a year before its release — that was really tough to deal with at the start of my career. Then I got the opportunity to go to LA and write with and for other people as well, and I just loved it.

You were there for a month, right?

Yeah, we were there for a month. Then we came back and did WAM Fest, and Fidelity festival in Perth. And then we did Falls, and moved to Sydney.

Work-wise, 2017 saw you traversing the country, and even getting intercontinental. What is it about Sydney that made it your more permanent home of choice?

In LA I was doing lot of writing and a lot of recording. The industry there is massive and there’s a lot of opportunity for collaboration. Sydney, to me, is the place in Australia that is most like LA — it’s where the industry is situated; there’s the most going on and the most people to work with. So it’s really the best place for me as a young musician building up a career, who’s trying to work with as many people as I can.

You were previously based in Perth, right?

Yeah. I grew up all over Australia really, but as an artist, I really consider myself to be from Perth. That’s where music for me really came to life. I started making music there when I was 15 with my brother’s friend, who’s now my manager. It was a slow start. Matt — my manager — always said that we didn’t want to sound like kids in a garage banging tin cans together, so we were careful to take the time to develop early on. So I was kind of hidden working behind the scenes for those first six years. Then he branched out and started working for (record label) Pilerats; while I graduated school, moved up to East Arnhem and started working with public health. After that I went to Perth and started studying medicine. At that time I met JCAL and started writing with him. At that same time Matt’s time at Pilerats ended and he started doing his own management stuff. That’s when we sat down in a café and I said, ‘So are you going to start managing me now?’ And he was like, ‘I knew this day would come.’

How do you manage the business of music? There’s a lot more than just writing songs to be done…

At the moment I’m independent, so in the last half of 2016 we got a publicist and a booking agent, who takes care of all the live stuff — the performances. It’s still pretty DIY, which is fun. And it’s helped me to understand what it is that labels do administratively.

Would you want to move to a label in the future or do you like doing it all yourself and with your team?

Maybe! It’s about finding the right fit and making sure that any people I work with understand what it is I’m trying to do. Particularly because everything that I’m trying to push is about equality and a certain political vision. I can’t have assholes working with that stuff; it just doesn’t make sense.

As you say, a lot of your work takes quite a firm political stance. Why do you think that music works as a platform for that kind of thought?

There’s a quote I heard the other day, and now I can’t remember who it’s from! But it said that ‘Sometimes the truth is too raw for people to handle, but that’s what the medium of art is for’. It’s an easier path into understanding. A lot of music is founded out of oppression, especially the styles of music that I do. It’s just more compelling than someone screaming in your face.

Your last release YKWD is so jumpy and groovy, but has quite serious lyrical content, right?

I love hip hop, but just because I love something doesn’t mean I don’t think there are some very serious issues with it. Hip hop is entrenched in misogyny and homophobia, and so this song is kind of an antidote to that. I truly believe that an attack on equality anywhere is an attack on equality everywhere, so it doesn’t make sense to say ‘yeah I care about black rights, but fuck women.’ So even though the song is fun and feel-good, it’s still a kind of a critique.

I was particularly impressed by Same Script, which addresses mental health, especially coming from a young man.

Gender roles are so entrenched for both men and women. The movement towards dissolving gender roles for women is so important, and while I would never speak on behalf, I will always echo and use my platform to spread wiser words from wiser women. But gender roles that compartmentalise us also affect men, and we don’t have enough men speaking about the problems that come out of that. It’s so important for everyone — of all genders — to feel comfortable speaking about mental health. Men, for example, are much more likely to take their own lives. And I certainly think not having the skills to communicate or feeling supported to communicate about our emotions and our vulnerabilities is a contributing factor in that.

Another thing that I’ve noticed is big on your social media, if not in your music, is your diet. Do you think veganism is something people can survive on?

Yeah absolutely, and not only survive, but flourish. Veganism I don’t think is necessarily a ‘diet,’ but a frame of mind. You can be a vegan and eat awful food, just Oreos and fries. But in terms of eating a plant-based whole food diet, there’s pretty strong evidence that that is what our physiology needs. Also, one of my favourite things about veganism is that sometimes you go somewhere and there may be one or two things on the menu, and if there isn’t you can usually say ‘Hey, just do whatever you can do’ and it’s really fun. Every now and then you get people who aren’t so stoked, but more often than not the chefs get really excited — they get to do stuff off-menu and they get to be creative. I love that. I wish I could take the same approach to clothes actually, just be told what to wear.

Wardrobe veganism, there you go! How do you go about what you wear onstage?

I like what fashion can do for self-expression, and for creating communities, but if I’m inside my house I can guarantee I’m naked. I guess I find it difficult to put stuff together. But if someone gives me something cool, I’ll wear it and love it. Levi’s gave me this jacket (gesturing to a light washed denim jacket thrown over a striped shirt). And then there’s op shop stuff, that’s really fun. Actually, I’ve been really into K-pop lately. There’s this group called BTS, and their fashion is amazing. And I’m like — if I had someone to just dress me like that, it’d be amazing.

What music do you listen to?

I listen to hip hop as a staple, and I grew up on a lot of reggae. But personally, probably one of my favourites is Beach House. They’re a duo — they do dream pop. I really like it because I find a lot of music is hard to listen to and not pick apart, but not Beach House.

Do you mean you pick apart things lyrically or musically?

Both. As a songwriter, it’s really hard to not just analyse, to ask ‘Oh how many bars have they done for the verse, pre-chorus, chorus? What instruments have they used? And what’s the lyric concept?…’ I found Beach House back in about 2010, because when The Weeknd was first coming out, he sampled them on his first mix tape. I have a love-hate relationship with him (The Weeknd), but anyway he’d sampled them and I always chase up the bands people have sampled. And so I found them through him and I was just really happy about it!

You work with samples too right? Not necessarily musical samples though, for example (prominent Indigenous journalist) Stan Grant. Does he know about that?

Yeah! His daughter messaged me a while ago actually. She found the song and liked it, and showed it to him, which was really cool.

How does listening to music fit into your day? Do you treat it like research, or part of your work? Or is it more organic and leisurely?

Actually, this is what I love exercise for. It’s hard to get a whole hour in the day — especially in this day and age where everything moves so fast — to sit down and listen to a whole album. So exercising is an opportunity to listen to the music I’m curious about and want to experience. And you don’t feel so bad because you really do need to exercise! I don’t curate up-tempo playlists to work out to, I just use the time to listen to what I’ve been wanting to listen to anyway.

2017 was so massive for you. So what’s next?

It’s funny. You kind of become desensitised because you’re always trying to go further. So something that you thought you would have lost you mind over, say, a year ago, happens, but you just focus on what’s happening in the future. On my grand master plan, I’m on like step two. There’s still so much I want to do.

Ziggy pulls us in for hugs before we leave, farewelling us on the doorstep of his home. He’s meeting Australian hip hop outfit Thundamentals this evening, ‘to hang out.’ A position as his wardrobe curator is currently available.

END

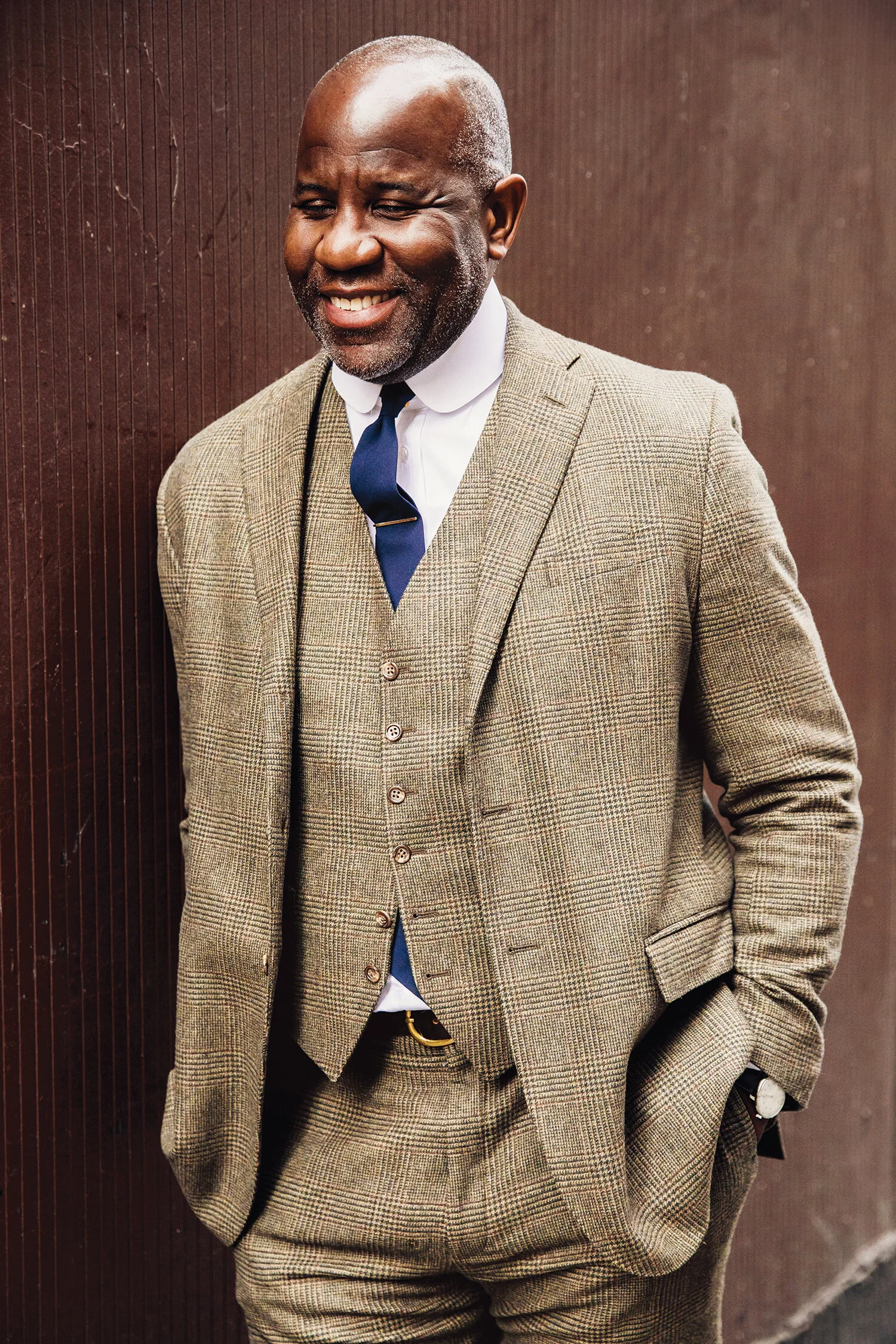

Ouigi Theodore in Brooklyn

Ouigi Theodore in Brooklyn

Published in print, March 2016.

Words by Andrew Geeves

Photography by Giuseppe Santamaria

Brooklyn is renowned for its straight-shooting inhabitants, tight-knit communities, and living sense of history. It is difficult to imagine a gentleman who could be more at home in Brooklyn than Ouigi Theodore — a menswear pioneer with his own boutique and brand, The Brooklyn Circus. MITT met up with Theodore to talk about fashion as an art form, stoop culture, and his 100-year plan.

“The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less,” stated the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, in 469 BCE. Fast-forward almost two and a half millennia, journey about 8,000km west, and zoom in on a corner store nestled between exactly the type of brownstones with external fire escapes that you would expect to see in picturesque Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. Here we find Ouigi Theodore, lover of people and owner of menswear boutique, The Brooklyn Circus, sitting on a bench outside his storefront with a twinkle in his eye, watching the world go by. “The reality is that the most beautiful and longest-lasting things come with the ability to say a lot more with less,” muses Theodore.

Connection and history are two of Theodore’s favourite talking points. “Through history, you get to see the things that actually lasted, the most beautiful aspects of humankind,” the bearded gentleman enthuses. Growing up in Brooklyn, Theodore was immersed in community from a young age. “What Brooklyn has that Manhattan lacks is a history of neighbourhoods,” he says. “When the high rises started to come up and get bigger in Manhattan about 30 years ago, they literally divided the communities. If you live in a 20-storey building, you never get to see your neighbours. In Brooklyn, there’s a higher chance of seeing your neighbour coming out of their home, parking their car, sitting on their stoop, going to the grocery store. That platform to interact creates community. People need community, which is why Brooklyn vibrates. Where are you having a block party in Midtown? It’s people living together, seeing how other people go about their lives, rather than being cooped up in their high-rise apartments. It’s the stoop. People come and join you. Brooklyn fosters stoop culture.”

While he revels in nostalgia, Theodore is also quick to seek out and recognise the beauty of people that he encounters in the present moment. “I just love people so much. In all aspects of life, when you meet [new] people, you just think, That guy is phenomenal, where is he from?,” he says. “That’s what is beautiful about a circus, all these crazy, weird folks. You don’t have to choose. You enjoy the whole experience! The circus is attractive to many different kinds of people—young, old, rich and poor. Everyone is all together.”

Thinking back to his childhood, Theodore reflects on the role that his relationship to clothing played in helping him curate his own circus of people. “Even as a teenager, I was always looking to connect with folks. When I was 15, I would get on a train and travel hours away to go to a remote store to buy something and then bring it back and wear it to school. Then, the conversation: ‘Where did you get that? I’ve never seen that! Is that Polo?’ For me, that was the excitement, the dialogue that resulted from that journey. People have always been at the centre of my creativity.”

Like his mother, grandmother and aunts before him, the ways in which Theodore relates to and uses clothing runs deeper than utility or trend. “It was about discovering another way to express yourself. It wasn’t about fashion. For all the women who raised me, it was about creating an extension of themselves through their dress. That’s what I try to do. I’ve never claimed to be this fashion guy…. When you are connecting with me, we’re not having conversations about fashion; we’re having conversations about style, character, history, and people,” he says. “My mother dealt in trade and was a socialite. I was introduced to this way of expressing myself by observing her ability to use what she was wearing and her appearance to communicate to others. My mother and grandmother were always very conscious of why they dressed the way that they dressed. If we were having dinner parties, my grandmother would wear a beautiful flowing housedress. She would lightly put on some jewellery that she’d had for years, and she never wore make-up. There was always a sense of glamour in her ability to not try to look glamorous. That is now in my thinking and everything that I do: how do you create this level of approachable glam?”

Theodore’s fondness for an approachable aesthetic underlies the philosophy behind his own personal style. “We’re in the fashion show business. The showmanship is cool, a lot of guys do it. They put on the nine-piece suit and the cape and the hat. They layer it on. I get it. I’ve done that at some point,” he says. “But when you really find yourself, how do you strip it all down and say ‘OK, this is what I really need?’ It’s more challenging and exciting to figure out the little nuances in what you’re wearing. It’s like a beautiful woman. Take off the make-up; let it be a dash of lipstick, a little blush on the cheeks. That’s really how I approach my style now.” He also strives to incorporate this less-is-more vision into his store and its eponymous clothing line. “People would say they were heavily inspired by The Brooklyn Circus, and I’d look at their space and say, ‘OK, you’ve got the look, but where is the character?’ I thought, Is that what we’re communicating? How do we simplify this?”

Now in its 13th year, The Brooklyn Circus sprang to life at the urging of one of Theodore’s friends. “I was in the nightlife business, promoting events and parties. I had a way of approaching things that wasn’t normal. When promoting events, I thought more about the package design...How do I make an invite that creates an experience? How do we get you involved in the party before you even attend the party? We did a bunch of full-experience parties. But I got to the point where I just wanted to design. I found an office space and started designing freelance,” Theodore recalls. “A good buddy of mine told me that people followed what I did and that I should put my perspective out there. He took me to a trade show and we walked around. I thought it was cool, but that there was a lot more that needed to be done. So I decided to give it a shot and it snowballed into all of this. I put my opinion into product and it just blossomed.”

The store, which looks like a library-cum-gentleman’s club with its dark wood paneling, antique cabinets, books, and vintage curios, started out selling third-party brands, and continues to carry a small, quality selection today, including Nisus Hotel from Japan and Merz B. Schwanen from Germany. “I always looked at it like the circus, putting things together and making them vibrate, like a cast of characters,” he says. “After a while, it was a little more difficult to find these things and I thought that I could design them. It worked out. Then the business aspect of it starts. You try to work out how to make money and survive. Now I’m at a point where I’m just trying to figure out how we can keep on having fun and continue to tell things from our perspective, incorporating our 100-year plan.”

Having a 100-year plan might sound unattainable, but it’s clear that Theodore’s plan is as well-considered as it is humble. “I don’t have this billion-dollar goal,” he says. “I’ve been on a yacht and I’ve had the finest wines. I’ve done all that stuff [but] I’m not a yacht kind of guy. The 100-year plan is wrapped around people and experiences and creating product that lasts. I love to buy our jackets back from people and to see that they have lasted. Our goal is to be creating the products that you will still have in 100 years’ time.”

This may seem an unusual sentiment in an era with such a strong emphasis on convenience, immediacy and disposability, but Theodore is not afraid to go against the grain. “I’ve never felt like I’ve fitted the mold,” he says. “The next chapter for us is definitely runway shows and presentations. I have more to say. When you look at the best designers in the business, they are clearly making statements. There’s a narrative. Do I want to come out and bow at the crowd and wave? No. But I’ve got 90 more years to go, and I’m thinking about how I can use that. I’m a huge fan of Thom Browne and Alexander McQueen and all of these guys that have been able to completely tell their story through what they do. I want to do that. I want to put that out to the world and see what they say.” And for Theodore, fashion is also the most natural medium with which to do that. “I can’t draw as well as I would like to draw. I can’t paint as well as I would like to paint. And I can’t shoot a picture to save my life. I can’t play music, but I do still have a tool, an artistic instrument that I can use. I will continue to walk straight and create beautiful things. This is my art form. For years I thought I wasn’t an artist. I fought with it. Then I realised, Dude, you’re an artist!”

As an artist, how does Theodore manage when he might be lacking in inspiration? “I try not to take myself and what I do too seriously,” he says. “The dark side of creativity in reference to the circus is the sideshow. Inspiration [comes from] being around people that allow you to speak your truth. You can constantly fight about whether you want to make money or create beautiful things. I want to do both. I’m an artist and a businessman. When you’re being honest about what you’re trying to say and where your ideas come from, there will always be room for inspiration.”

END

Off The Cuff with Ali: Imagination

This week, we’re taking a mid-season break from the Portrait Session podcast and instead presenting you with a bonus episode of Off the Cuff with Ali. The event took place a couple weeks ago as part of the Reigning Men exhibition at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney. With an audience of over 40 guests, Ali brought his column in MITT issue 9 to life, as he looked at prominent movements in art and fashion, exploring how they affected one another, and continue to shape our contemporary imagination.

Men In This Town reading Men In This Town

Men In This Town reading MITT

JOSH BEGGS IN SYDNEY

Josh Beggs in Sydney reads 'The Curious Frames of Saul Leiter', written by Tomas Leah and originally published in MITT magazine issue 1, March 2015.

Become a MITT magazine subscriber and make sure you don't miss any future issues!

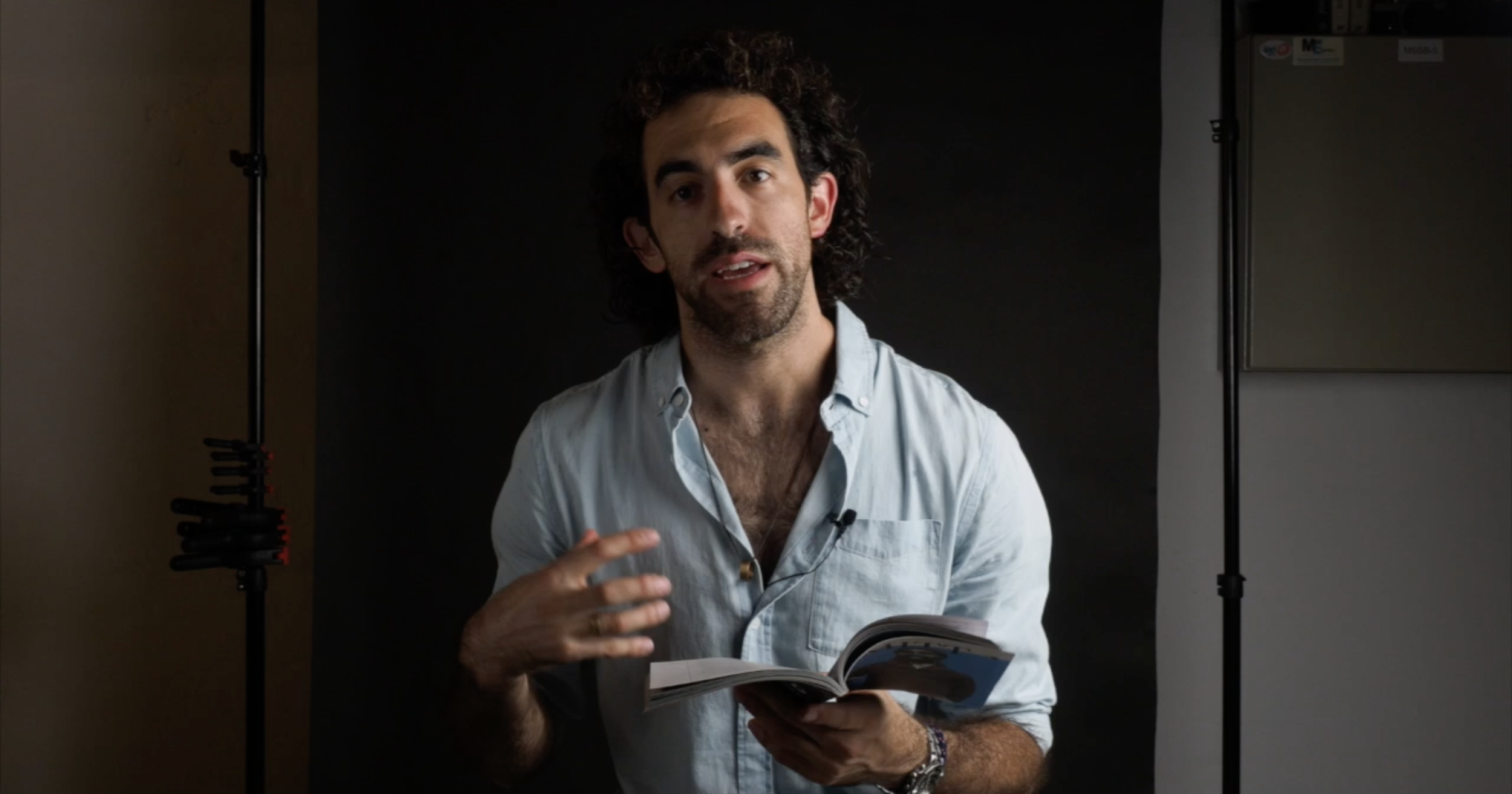

Men In This Town reading Men In This Town

Men In This Town reading MITT

NICHOLAS FERRARIS IN SYDNEY

As part of a new series, I've decided to give second life to the archived issues of MITT magazine by recording men in this town reading some of my favourite features from the now sold out editions.

This week, Nicholas Ferraris in Sydney reads 'Ouigi Theodore in Brooklyn', written by Andrew Geeves and originally published in MITT magazine issue 4, March 2016.

Become a MITT magazine subscriber and make sure you don't miss any future issues!

Off the Cuff with Ali: Emperor’s New Clothes

Emperor’s New Clothes

OFF THE CUFF WITH ALI

Off The Cuff with Ali returned to Fine Fellow last week as Ali Asghar Shah led a discussion on his latest column in MITT magazine issue 8; Emperor's New Clothes.

“Objects are only what we make of them and only attain value when we give it to them. Therefore, the popularity of these brands is only a consequence of our endorsement.”

For those of you who couldn't make it, watch a short film from the night by Kris Andrew Small above and a recording of Ali's full talk below.

Get MITT magazine issue 8.

Pre-order MITT magazine issue 8

It’s hard to believe but the 8th issue of MITT magazine is here and available to pre-order! 🎉 This issue features some truly amazing works by men in this town including cover man Dani Bumba in Paris, Jonathan Daniel Pryce in Glasgow and Micke Lindebergh in Sydney.

To make sure you don’t miss this issue or any future issues of MITT, become a subscriber for just $10 and get free shipping on all future deliveries, worldwide!

And as always, your support means the world, so thank you for visiting Men In This Town and following along all this time! 😊

— Giuseppe